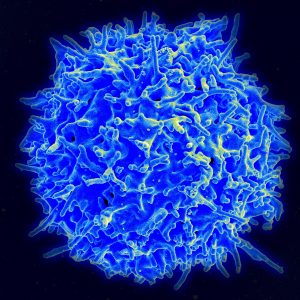

A T cell is a type of lymphocyte, which develops in the thymus gland (hence the name) and plays a central role in the immune response. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell receptor on the cell surface. These immune cells originate as precursor cells, derived from bone marrow, and develop into several distinct types of T cells once they have migrated to the thymus gland. T cell differentiation continues even after they have left the thymus.

Groups of specific, differentiated T cells have an important role in controlling and shaping the immune response by providing a variety of immune-related functions.

One of these functions is immune-mediated cell death, and it is carried out by T cells in several ways:

- CD8+ T cells, also known as “killer cells“, are cytotoxic – this means that they are able to directly kill virus-infected cells as well as cancer cells. CD8+ T cells are also able to utilize small signalling proteins, known as cytokines, to recruit other cells when mounting an immune response.

- A different population of T cells, the CD4+ T cells, function as “helper cells“. Unlike CD8+ killer T cells, these CD4+ helper T cells function by indirectly killing cells identified as foreign: they determine if and how other parts of the immune system respond to a specific, perceived threat. Helper T cells also use cytokine signalling to influence regulatory B cells directly, and other cell populations indirectly. Regulatory T cells are yet another distinct population of these cells that provide the critical mechanism of tolerance, whereby immune cells are able to distinguish invading cells from “self” – thus preventing immune cells from inappropriately mounting a response against oneself (which would by definition be an “autoimmune” response). For this reason these regulatory T cells have also been called “suppressor” T cells. These same self-tolerant cells are co-opted by cancer cells to prevent the recognition of, and an immune response against, tumour cells.